What are pathogenic fungi?

Pathogenic fungi are types of fungi that can cause diseases in humans and animals. These fungi have the ability to invade host tissues and can effectively overcome the host’s immune defences, leading to infections.4

Four features of fungi

There are four key features that set fungi apart from other organisms:1

Saprophytic or parasitic

Obtain energy from decaying or living matter.

Structurally simple

Basic structural unit, either hyphae or single cells.

Heterotrophic

Secrete enzymes for external digestion; nutrients are then absorbed through the cell wall.

Eukaryotic

Rigid cell wall and DNA is contained within the nucleus.

Characteristics and morphology of pathogenic fungi

Pathogenic fungi can have different morphologies: yeasts and moulds. Some can switch between these morphologies, which are known as dimorphic fungi.5,6

Pathogenic fungi can have different characteristics that can enable them to thrive within human hosts. This can include their ability to withstand high temperatures, invade human tissues, break down and absorb host tissue, and evade the human immune system.7

Understanding the structure of pathogenic fungi is essential, as it plays a key role in their interactions with the host and their ability to cause disease.8

The fungal cell wall is a key defining feature of fungal cells;4,8,9 it consists of outer mannoproteins, followed by a β-glucan layer, a chitin layer and an inner cell membrane layer.8 The unique nature of the fungal cell wall makes it an ideal drug target.9

Yeasts, e.g. Candida:4–6

- Grow as single cells

- Usually reproduce by budding (asexual reproduction)

- Usually form smooth, flat, conically shaped colonies

Moulds, e.g. Aspergillus:4,5,7

- Multicellular, organised into hyphae, with/without cross walls or branching

- Asexual or sexual reproduction

- Colonies usually appear fuzzy

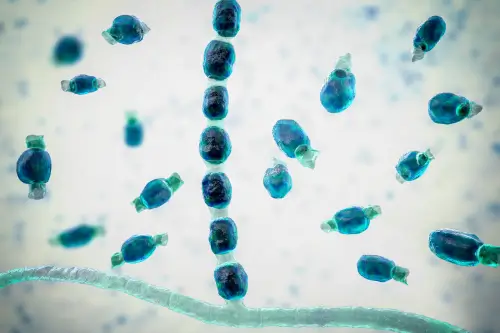

Dimorphic fungi, e.g. Coccidioides4,5

- Grow in two distinct morphological forms, correlating with the saprophytic and parasitic modes of growth

- They grow as moulds in vitro (20–25°C), and as either yeast cells or spherules in vivo (37°C)

How do pathogenic fungi cause disease in humans?

Fungi can enter a host organism through two primary routes: by breaking the skin barrier or being inhaled13 Once inside the host, pathogenic fungi can employ various strategies to cause infection.4

Pathogenic fungi produce a range of enzymes that degrade host tissues, facilitating their invasion and spread throughout the body.7 Some pathogenic fungi can produce mycotoxins, which are toxic compounds that can cause harmful effects on human cells and tissues, further exacerbating the infection and contributing to symptoms.14

As the pathogenic fungi invade tissues, they disrupt normal cellular functions, which can trigger an immune response from the host.4 However, some pathogenic fungi have developed strategies to evade or suppress the host’s immune response, allowing them to persist and proliferate within the host despite immune efforts to eliminate them.4

The severity of diseases and infections caused by pathogenic fungi can vary, depending on factors such as the amount of fungal inoculum introduced into the host, the extent of tissue damage caused by the fungi, their capacity to reproduce within the host environment, and the overall immune status of the host.13

Individuals with compromised immune systems, for example, are often more susceptible to severe invasive fungal infections, while a healthy immune system may be able to control and contain the spread of the fungi.15

Fungal infections are sometimes classified as either opportunistic or primary:10

Opportunistic

Infections that mainly occur in immunocompromised hosts

Primary

Infections that can develop in immunocompetent hosts, and usually result from inhalation of fungal spores

Types of fungal pathogens in humans

There are several fungal pathogens that can cause diseases in humans, ranging from superficial skin infections to life-threatening systemic infections, especially in immunocompromised individuals.15 Some of the invasive fungal infections in humans include:

Mould infections

Invasive aspergillosis (IA)

Mucormycosis

Rare mould infections

Eumycetoma

Fusariosis

Lomentosporiosis

Scedosporiosis

Dimorphic fungal infections

Coccidiomycosis

Histoplasmosis

Paracoccidioidomycosis

Talaromycosis

Yeast infections

Cryptococcosis

Invasive candidiasis (IC)

Yeast-like infections

Pneumocystis pneumonia (PJP)

WHO list of fungal priority pathogens

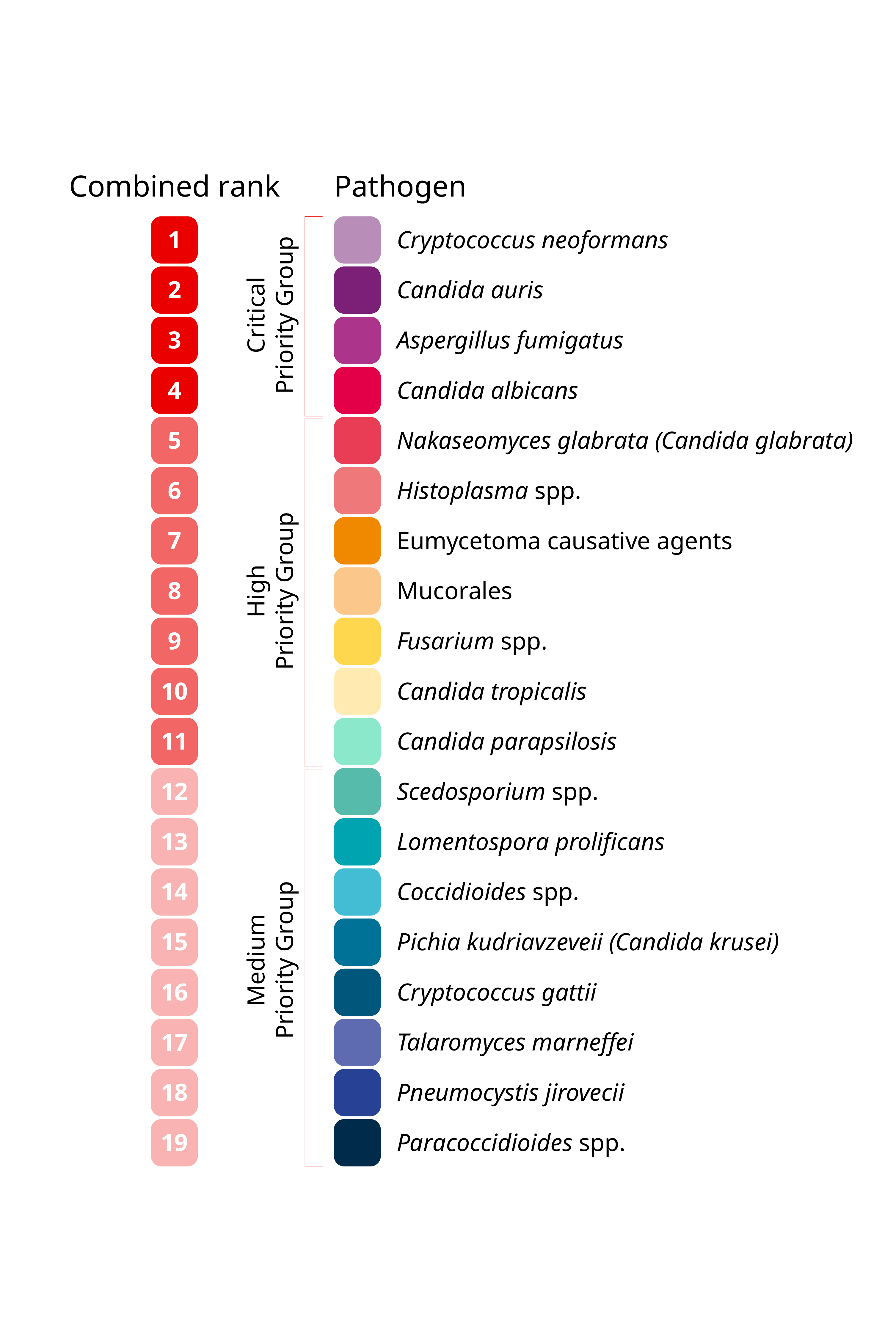

Fungal pathogens are emerging as a critical global health concern, particularly with the rise of drug-resistant strains such as Candida auris.17

In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recognised this growing threat and has developed a fungal priority pathogens list to highlight the most significant fungal species that pose a threat to human health.18

These were based on 10 assessment criteria, which include (listed in no particular order) antifungal resistance, fatality rate, annual incidence, inpatient care, and access to diagnostics.18

A list of fungal priority pathogens was developed, ranked in order of priority from critical to medium. An overall combined ranking was based on a discrete choice experiment global survey for research and development priorities and best–worst scaling for public health importance.18

Some of the pathogens are confined to certain geographical areas or specific populations and thus may not be considered a priority on a global scale; however, they must be considered in the local context.18

WHO fungal pathogen priority list

Figure 1: A graph showing the 19 fungal pathogens that were ranked and categorised into three priority groups (critical, high and medium).

Discover more about diagnostics

Comprehensive information on the different methodologies used to diagnose IFDs, and guidance on how to interpret the results of diagnostic tests.

References

- Moore D, Alexopoulos CJ. Fungus [Internet]. Encyclopedia Britannica. 1999 [cited 2024 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/science/fungus

- Loron CC, François C, Rainbird RH, Turner EC, Borensztajn S, Javaux EJ. Early fungi from the Proterozoic era in Arctic Canada. Nature. 2019 Jun;570(7760):232–5.

- Fisher MC, Gurr SJ, Cuomo CA, Blehert DS, Jin H, Stukenbrock EH, et al. Threats posed by the fungal kingdom to humans, wildlife, and agriculture. MBio [Internet]. 2020 May 5 [cited 2024 Oct 7];11(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32371596/

- Hernández-Chávez MJ, Pérez-García LA, Niño-Vega GA, Mora-Montes HM. Fungal strategies to evade the host immune recognition. J Fungi (Basel) [Internet]. 2017 Sep 23 [cited 2024 Oct 7];3(4). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5753153/

- McGinnis MR, Tyring SK. Introduction to mycology. In: Medical Microbiology. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996

- Shrestha A. Difference Between Yeast and Mold [Internet]. Microbe Online. 2022 [cited 2024 Oct 7]. Available from: https://microbeonline.com/difference-between-yeast-and-mold/

- Angiolella L. Virulence regulation and drug-resistance mechanism of fungal infection. Microorganisms. 2022 Feb 10;10(2):409.

- Arana DM, Prieto D, Román E, Nombela C, Alonso-Monge R, Pla J. The role of the cell wall in fungal pathogenesis: Fungal cell wall in pathogenesis. Microb Biotechnol. 2009 May;2(3):308–20.

- Gow NAR, Latge JP, Munro CA. The fungal cell wall: Structure, biosynthesis, and function. In: The Fungal Kingdom. American Society of Microbiology; 2017. p. 267–92.

- Hasim S, Coleman JJ. Targeting the fungal cell wall: current therapies and implications for development of alternative antifungal agents. Future Med Chem. 2019 Apr;11(8):869–83.

- Vulin C, Di Meglio JM, Lindner AB, Daerr A, Murray A, Hersen P. Growing yeast into cylindrical colonies. Biophys J. 2014 May 20;106(10):2214–21.

- Cole GT. Basic biology of fungi. In: Medical Microbiology. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996.

- Kobayashi GS. Disease mechanisms of fungi. In: Medical Microbiology. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996.

- Bennett JW, Klich M. Mycotoxins. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003 Jul;16(3):497–516.

- Low CY, Rotstein C. Emerging fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. F1000 Med Rep. 2011 Jul 1;3:14.

- Walsh TJ, Dixon DM. Spectrum of mycoses. In: Medical Microbiology. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996.

- Sikora A, Hashmi MF, Zahra F. Candida auris. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2022 [cited 2024 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060241